Extracting Information from Material Science Articles

Published:

This article briefly introduces my work on information extraction from material science articles, which is decided to not be published as a serious conference/journal paper due to quality concerns (i.e., insufficient innovation/impact). But I figure it would be helpful to make it partly available to everyone in case it might be helpful or inspiring to someone who’s doing similar work. The code is available in this GitHub repo.

Abstract

Machine learning models can significantly accelerate polymer design by providing reliable predictions for material properties without the need for wet lab experiments. However, manually constructing large-scale annotated datasets to train such models can be prohibitively difficult and time-consuming. Although efforts have been made to develop Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques for extracting information from literature data, these models usually require a significant amount of annotated data to train the extraction models effectively. We propose an active learning-based model learning scheme that minimizes human effort in the information extraction pipeline. We start with simple labeling rules to collect an initial set of noisy labels, a subset of which are then presented to material science experts to correct labeling mistakes. Using this small set of labels, we train an information extraction model that extracts more data for collection and refinement, which is repeated over the candidate data points. This active learning scheme significantly reduces human effort, as judging the correctness of an annotation is much more efficient than searching for entities in articles. Experiments on ring-opening polymer property extraction show that our pipeline in total contributes 58 new data points to the property prediction dataset within half of the time for people to annotate from scratch without the assistance of our information extraction model. The new data points are proven effective in reducing the enthalpy prediction error by 2.94 root mean square error of a machine learning model.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been a remarkable advancement in material science technologies, leading to an explosion of experimental results on various types of materials. Moreover, advanced machine learning (ML) models have emerged as promising tools for material science experts to estimate the properties of new materials directly. These models can also aid in the design of wet lab experiments to accelerate the verification of predicted properties. However, the construction of reliable ML models requires a sufficiently large training dataset, which can be challenging to acquire due to the scattering of relevant data points across numerous published literature. Building such a dataset demands a considerable amount of work for locating informative papers and sentences, which is prohibitively challenging and time-consuming.

ML-based information extraction (IE) techniques have been developed by researchers to automatically locate relevant entities and elements within documents. These techniques are adapted and customized to fit the material science domain. IE techniques enable the processing of a large number of candidate documents in a short time, extracting the desired polymer property mentions while discarding irrelevant documents with relatively high precision. Such approaches significantly improve workflow efficiency and facilitate the discovery of easily-overlooked information hidden in the corners of papers. However, ML-based IE models used in previous works suffer from the same limitation as other supervised ML approaches, i.e., they require large-scale manually labeled datasets to achieve high performance. The lack of such data is the very reason why IE methods are used in the first place. One workaround is weak supervision, which employs dictionary matching or multiple simple heuristic rules to generate weak labels before aggregating and denoising them into one label set with unsupervised methods such as hidden Markov models. Although weak supervision approaches have shown promising performance in denoising noisy input labels, they still cannot fully address the gap caused by annotation quality. While labeling functions are quicker to construct initially, the marginal revenue from labeling new data points exceeds that from designing new labeling functions after several iterations of label annotation/labeling function application.

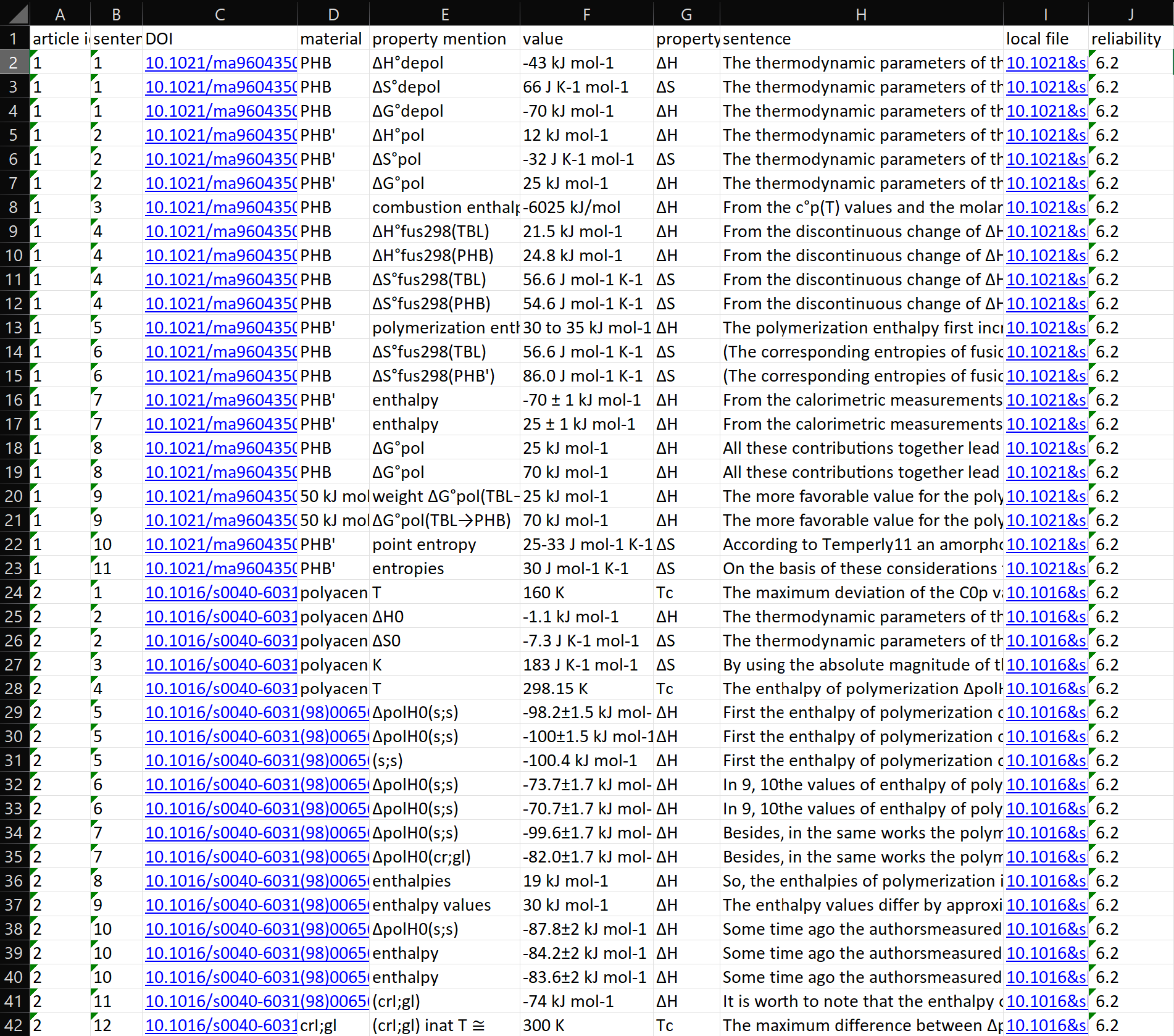

|

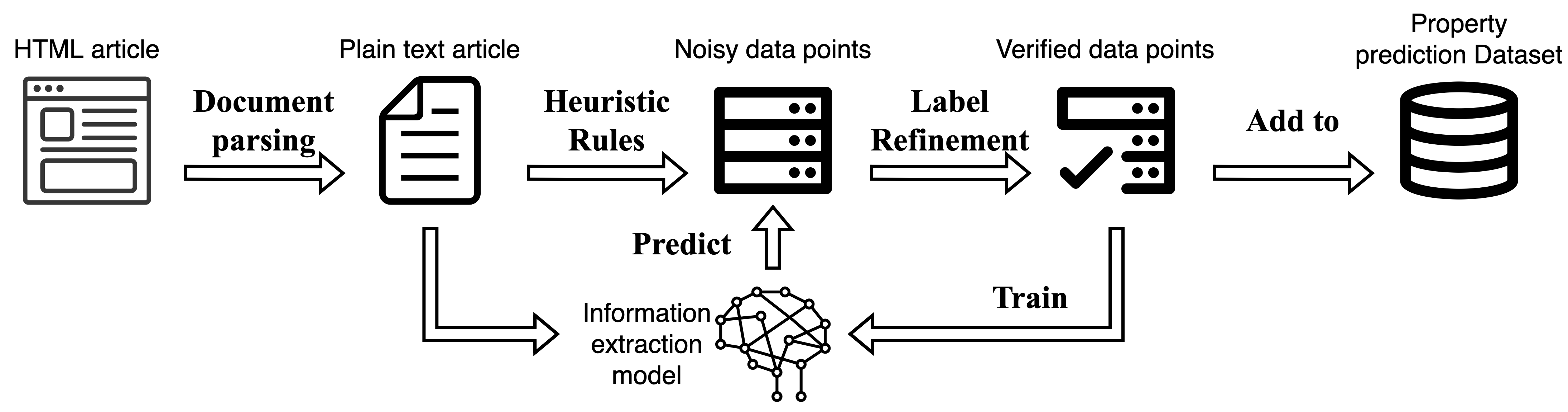

| Figure 1. The pipeline of human-assisted information extraction from material science papers. |

We propose an IE pipeline based on the active learning schema, as shown in Figure 1, to minimize human annotation effort without compromising model performance. Similar to weak supervision approaches, we begin with simple labeling functions to provide an initial set of weakly annotated labels. Rather than training models directly with these weak labels, we select a small subset of the annotated data and present them to human annotators for correction. An ML model is then trained on the refined subset and applied to the article corpus to gather more data points with higher precision. The annotation-training cycle is repeated several times until the supervised model no longer improves significantly with an increasing amount of training data. Compared with annotating from scratch, correcting labels is an easier and more efficient task for human annotators as the range of input sentences is limited. The active learning pipeline significantly reduces the human effort required to obtain results with comparable performance.

In previous research, data extraction from article abstracts, which often contain key information of interest, has been the focus due to their simplified format and availability on publisher websites. However, the limited nature of abstracts means that they may not capture the detailed discussions necessary for material property extraction. Other work in the inorganic materials domain has attempted to extract specific properties from the body of the paper using a rules-based parser such as the ChemDataExtractor framework. In our work, we propose to expand the extraction pipeline to include the article bodies, which requires the development of a custom article parser to maintain the semantic and structural information in the original paper. Rather than using off-the-shelf parsers, we create a parser tailored for each publisher to ensure cleaner parsing results, and our experiments show the superiority of this approach in case studies.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed pipeline, we evaluate its performance in extracting thermodynamic data related to ring-opening polymerization (ROP). ROP is a reaction that creates polymers from cyclic monomers and is of particular interest to the polymer science community due to the potential for developing chemically recyclable polymers. The development of such polymers is crucial in addressing the global plastic waste crisis. Moreover, the chemical space of ROP-derived polymers is vast, offering flexibility to discover polymers that are both chemically recyclable and mechanically robust enough to replace commodity plastics. Specifically, the proposed IE pipeline is used to extract the enthalpy and entropy of polymerization, as well as the ceiling temperature ($\Delta H$, $\Delta S$, and $T_{c}$ respectively) of ROP polymer materials. These properties were selected as they are essential for determining the chemical respectability of ROP polymers. Focusing on ROP polymers also presents a challenging and specific IE task, as thermodynamic data from other polymerization types can appear similar in sentences, and there is limited available data in the literature. Therefore, by applying to extract thermodynamic data for ROP, the IE pipeline can be well validated, performance metrics can be captured, and data for creating ML models to screen polymers for chemical recyclability can be extracted for future use.

In summary, our contribution is threefold:

we develop an advanced material science paper parser that leads to more accurate parsing results and better content coverage;

we propose an active learning-based information extraction pipeline that achieves promising performance with minimal human involvement; and

we validate our system on the specific task of identifying thermodynamic properties within the scientific literature and demonstrate the effectiveness of our system in providing valuable data for the development of machine learning models to screen polymers for chemical recyclability.

2. Method

This section discusses our information extraction pipeline, which includes 3 steps: 1) document parsing, 2) heuristic extraction and 3) label refinement with active learning.

2.1. Document Parsing

To facilitate the later information extraction process, our first step was to design a program that parses research articles in HyperText Markup Language (HTML) and Extensible Markup Language (XML) into machine-readable data structures. We choose HTML/XML over PDF because almost all recent articles have HTML/XML formats available, which provide cleaner content than the PDF format. While previous works, such as ChemDataExtractor, have developed general-purpose parsers, their quality is suboptimal due to a lack of publisher-wise fine-tuning. Specifically, existing parsers struggle to distinguish section titles, image captions, or special components such as citations from informative article paragraphs. This results in incorrect sentence/paragraph splits, which can jeopardize the subsequent semantic encoding steps. In contrast, our parser is tailored for each publisher and achieves cleaner parsing results, leading to better overall performance.

On the contrary, our article parser is designed to focus on several prominent online publishers where the majority of influential material science articles are published, including AAAS, ACS, AIP, Elsevier, nature, Royal Society of Chemistry, Springer, and Wiley. By focusing on a narrower range of publishers, we can tailor our parser for each one, taking into account their unique article formats and structures. This enables us to accurately distinguish titles, abstracts, paragraphs, images, and table captions from each other. Additionally, our parser is capable of converting tables into machine-comprehensible data structures without losing any structure or content information, provided such information is available in the original documents.

We also take great care in normalizing the web contents by filtering out uncommon Unicode hyphens and invisible characters, unifying characters with the same semantics, and removing redundant white spaces and new lines. This step removes distractions from the corpus and helps labeling rules and supervised models to discover more distinct features, thus promoting the performance of information extraction.

2.2. Information Extraction with Labeling Rules

Equipped with machine-comprehensible paper content, the next step is to design labeling functions (LFs) to provide an initial set of annotations, which we can manually refine and use to train supervised models. High-quality LFs are desirable as they greatly reduce human effort. However, it can be challenging to come up with such rules since the quality of annotations varies depending on the ambiguity of the target information, the difficulty of the specific IE task. In the following paragraphs, we discuss the target information to extract and the labeling rules we adopt to achieve the best annotation quality.

Problem Setup

The IE process consists of two main tasks: named entity recognition (NER) and relation extraction (RE). NER aims to classify each token in the input text sequence into predefined categories, such as Material Name, Property Name, Quantity, or O (which indicates that the current token is of no interest). From another perspective, NER locates the spans of the tokens that belong to specific entity categories. RE, on the other hand, links the identified entities to form relation tuples. For instance, given a material entity and a property entity, we can associate them using RE techniques and claim “this specific material has this specific property”. In our work, we focus on extracting not only Material Name, Property Name, and Quantity entities, but also their relation tuples. Specifically, we aim to extract the property values of certain types of materials from the scientific literature.

Recognizing Named Entities

Quantity A Quantity entity comprises two sub-types: Number and Unit. Detecting numbers, including decimals such as “12.34”, negative numbers such as “-12”, and ranges such as “12 – 34”, is a relatively simple task that can be accomplished using simple regular expressions. The only potential source of ambiguity comes from citation numbers, which can be excluded with acceptable accuracy in the subsequent relation extraction step.

One desirable attribute of the Unit entity type is that it is possible to construct a finite set that contains all possible unit keywords associated with a specific property. This enables us to manually compose a look-up dictionary for each property, such as “[K, ]” for temperatures, and perform direct keyword matching. Keyword matching generally prioritizes precision over recall (coverage), which is more appropriate for a “human-in-the-loop” system.

Property Name Similarly to Unit, it is practical to enumerate all possible forms of a Property Name or express it as regular expression patterns and apply keyword matching to identify such entities in the article paragraphs. For instance, the property “ceiling temperature” is usually referred to in the papers as “ceiling temperature” itself or the abbreviation “$T_{\rm c}$”, and we look for such keywords to label them as Property Name entities. However, multiple properties can share the same abbreviation, causing confusion for the labeling function and leading to false positives. Rather than addressing this issue here, we handle it with the supervised ML model in subsequent steps. The ML model is more capable of contextual comprehension and can understand the actual meaning of an expression.

Material Name Constructing labeling functions (LFs) for material names is a complex task due to the lack of clear lexical features that distinguish material names and the absence of a comprehensive dictionary containing all variants of material names. As a result, we adopt three LFs to identify material names, including:

a BERT-based NER model trained on the dataset provided by @shetty2021automated;

the material named detector integrated with the ChemDataExtractor, which is also rule-based but complex enough to handle most real-world scenarios with decent performance; and

a keyword matcher powered by a small dictionary containing frequently appeared material names.

While these LFs are mostly complementary, they can occasionally generate entity spans that partially overlap with one another. In such cases, we resolve the conflict by selecting the largest span as the final Material Name entity.

Extracting Relations

The purpose of the RE step is to group the extracted entities into relation tuples of the form <Material Name, Property Name, Quantity>, which represents “the property of this material equals to quantity”. The Quantity entity consists of a pair of <Number, Unit> and should be the first relation to be identified. In practice, we consider a pair of Number and Unit entities to be a valid Quantity entity if the gap between them is less than 5 characters, with the Number entity appearing first. To link the Property Name to the Quantity, we look for the Property Name entity that appears in the same sentence as the Quantity with the shortest distance counted by tokens. As the last element of the tuple, we consider the last Material Name entity appearing before the Property Name in the same paragraph as the subject of the property.

2.3. Label Refinement and Active Learning

As mentioned in the previous sections, the output from labeling functions (LFs) is not sufficiently clean to be added directly to the property prediction dataset that we aim to build. The main source of errors is due to property synonyms and incorrect linkages among material names, property names, and quantities, which are difficult, if not impossible, to avoid by improving the labeling functions alone. To address this issue, we incorporate a machine learning (ML) model to remove false positives and pick up instances that were potentially missed during the LF annotation due to incomplete keyword dictionaries.

While there are some studies that investigate training ML models directly with noisy labels, they are still unable to achieve performance on par with ML models trained on clean labels. Since our IE task is more application-driven, it is necessary to manually refine the noisy labels to get the best performance from the ML models.

Label Refinement

Instead of correcting individual entities, we have opted for a more user-friendly label refinement approach, which involves correcting sentence annotations. This change reduces the minimal element to annotate from tokens to sentences, and it is feasible because we require the Property Name to appear within the same sentence as the Quantity. Accordingly, we consider sentences containing <Property Name, Quantity> pairs as positive, and all others as negative.

We present the set of sentences labeled as positive by LFs, along with the corresponding articles, to material science experts. By examining the sentences and their context, the experts determine whether the positive labels are correct, i.e., whether they represent true positives or false positives. We add the entities from the true positive sentences to the property prediction dataset, while discarding those from the false positive sentences.

Model Training

Dataset The label refinement step naturally generates a dataset containing positive sentences (true positive LF results) and semantically similar negative sentences (false positive LF results). The similarity between the negative and positive instances makes it challenging for human annotators to distinguish them without referring to the context. To further challenge the model, we also randomly sample several negative sentences from the article to create the remotely negative set. The remote set aims to teach the model to differentiate between common, uninformative sentences and positive instances.

Model Architecture We leverage the power of Transformer-based models, such as BERT or RoBERTa, which are large pre-trained language models (PLMs), for the sentence classification task. PLMs are typically models with hundreds of millions of parameters pre-trained on corpora with a scale of billions, using objectives such as masked token prediction. Due to their size and pre-training, PLMs have the ability to comprehend natural language, making them particularly effective when fine-tuned on small datasets. These models map each word/token in natural language to a high-dimensional real-valued vector, known as a "token embedding", which is more interpretable by machines. Tokens with similar semantic meanings are usually clustered together in the Euclidean space where the embeddings are defined. We choose BioBERT, a variant pre-trained on biomedical and chemistry corpora, as it is better suited to understanding material science papers than general-domain BERT models.

Model Fine-Tuning

The BioBERT model is fine-tuned using binary sentence classification, following the conventional BERT-for-sentence-classification setup proposed by @Delvin-2019-bert. To this end, models in the BERT family prepend a special token [CLS] to each tokenized input sentence. This token is regarded as the representation of the whole sentence, with its embedding carrying the corresponding semantics. A classification layer is then appended to the sentence embedding to perform the classification operation. This layer maps the high-dimensional vector to a 1-dimensional real-value scalar, which is converted through a sigmoid function to a probability sample within the range $(0,1)$ representing the probability of the sentence being positive. The model parameters $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ are updated by minimizing the negative log-likelihood between the true label $y_i\in{0,1}$ and the predicted probabilities $p_i \in (0,1)$ using gradient descent, resulting in the following loss function:

where $N$ is the number of total data points in the dataset and $i\in {1,2, \dots, N }$ is the instance index. After fine-tuning, the probability $p_i$ is passed through a threshold $\eta$ to decide whether the input sentence is predicted as positive, i.e., $\hat{y}=1$. This is achieved through the following equation:

\[\hat{y} = \mathbb{I} (p_i > \eta),\]where $\eta$ is typically set to 0.5, but can be adjusted to acknowledge precision or recall requirements.

2.4. Active Learning

To reduce the human labor required for refining hundreds of LF outputs in one shot, we adopt an iterative active learning scheme that leverages fully supervised models, which perform better with more training data, especially when the size of the initial dataset is small. Our approach involves first selecting a small set of high-confidence LF outputs, refining their labels, and fine-tuning the BioBERT model. Next, we apply BioBERT to the original corpus and generate a new set of positive sentences that contain the <Property Name, Quantity> entity pairs. The new data points are ranked by confidence scores, and the top-$K$ data points that have not appeared in the previous dataset are selected for annotation. We repeat this process several times until we have exhausted the high-confidence positive predictions or have achieved the desired dataset size for property prediction.

3. Results

|

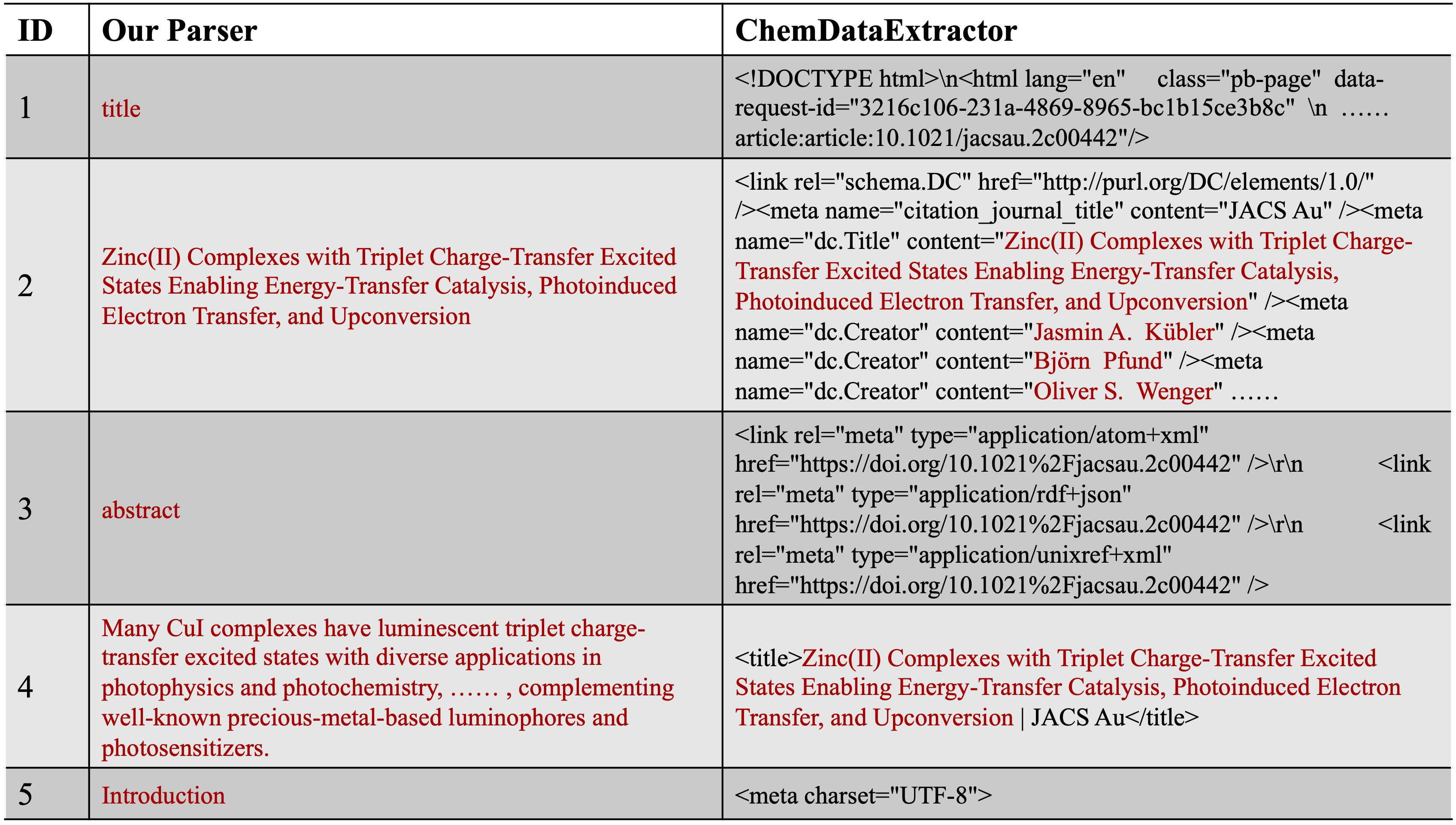

| Figure 2. The first 5 article elements extracted from a work recently published by using our parser and ChemDataExtractor, respectively. Useful contents are marked as red. For better demonstration, we substitute some strings with “……”. |

3.1. Document Parsing

To demonstrate the superiority of our document parser, we compared its parsing results with those of ChemDataExtractor, a popular document processing framework widely used in recent works, on a publicly available paper. Figure 2 shows the first five article contents extracted by each parser. Our parser successfully removes all decoration characters while keeping the main content complete, clean, and ordered. In contrast, ChemDataExtractor fails to do so, resulting in messy results where the article content is submerged by meaningless characters, hindering the following information extraction step.

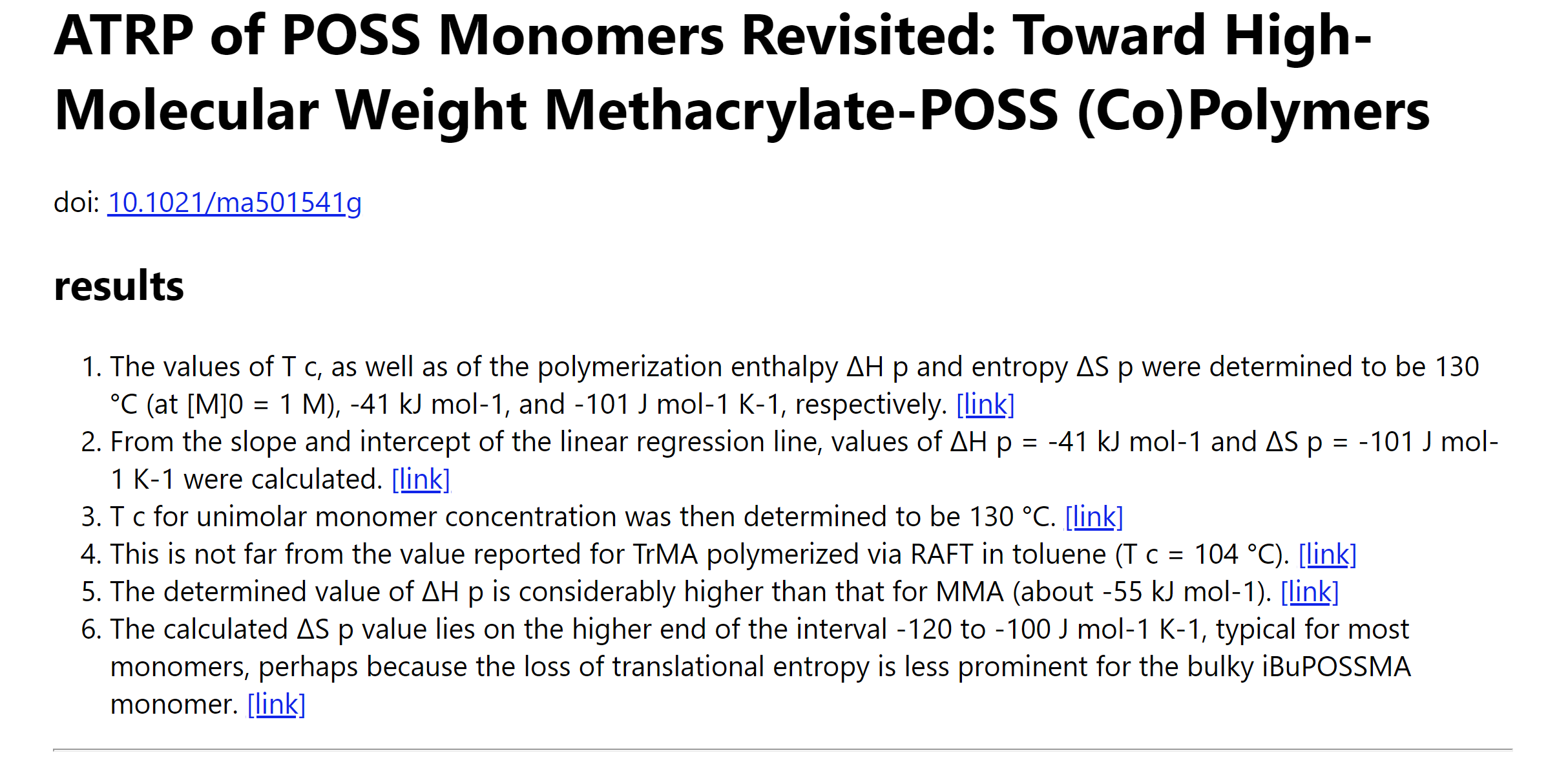

|

|

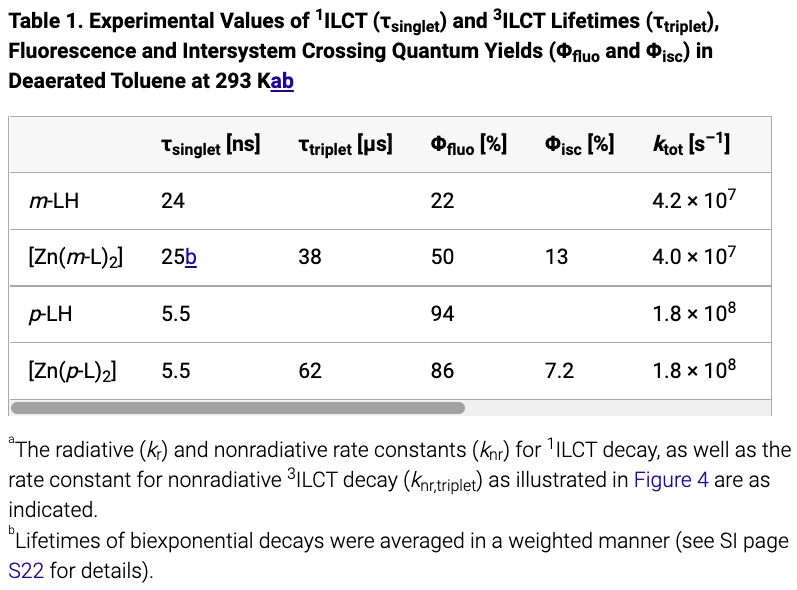

| Figure 3. Table parsing results. The first figure is the original table and the second one is the parsed result. |

In addition, we present the table parsing results in Figure 3. Our parser successfully preserves all table content, including the table caption, footnotes, and table content, with only minor format differences such as missing superscripts when compared to the original tables presented on the HTML webpage. This achievement is significant as it will facilitate information extraction not only from the plain text but also from article tables, providing additional sources of information and resulting in better extractor coverage.

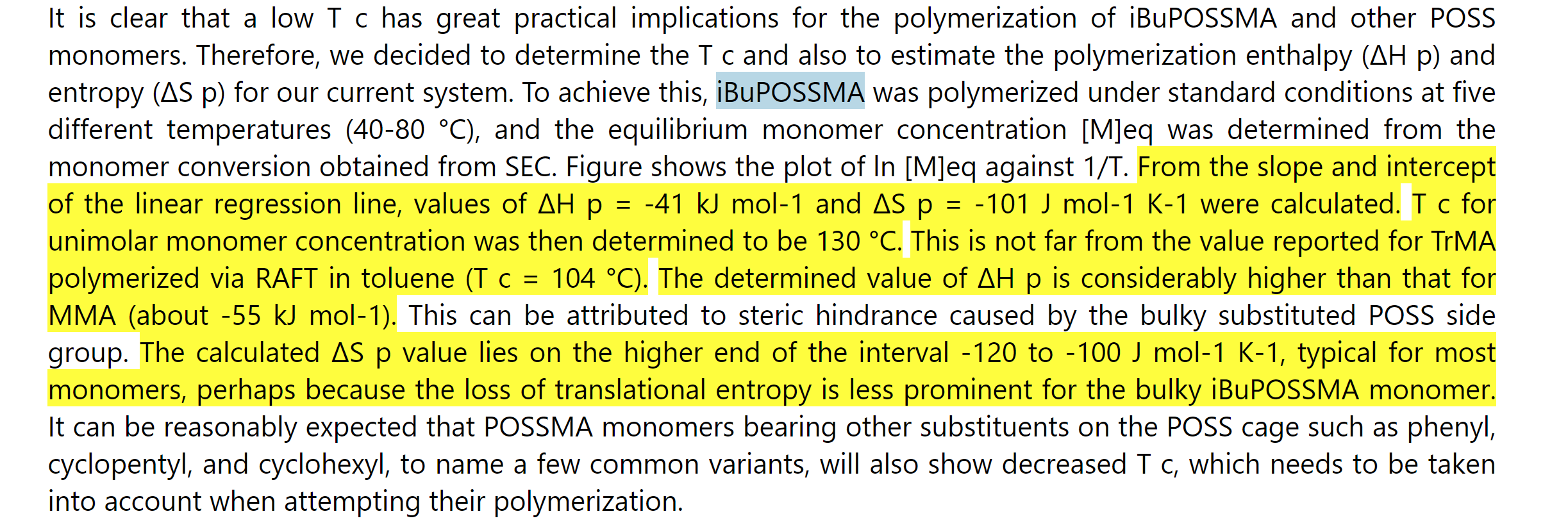

|

|

|

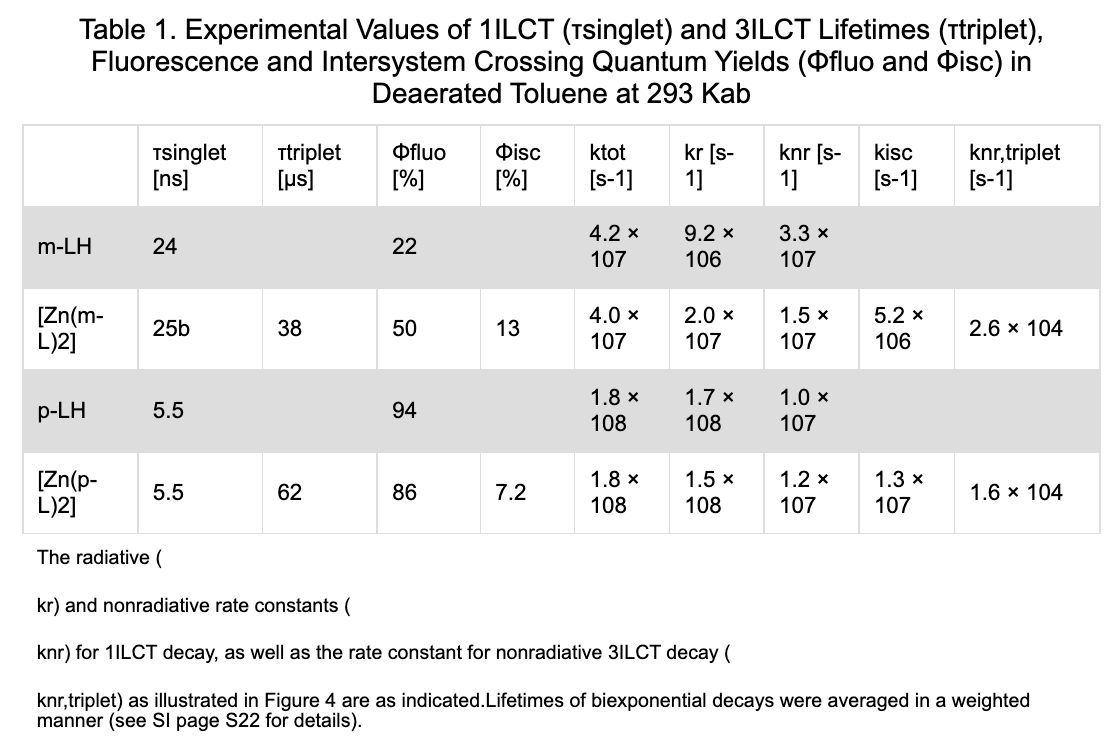

| Figure 4. An example of presenting information extraction results as Microsoft Excel table and HTML files. The tree figures are Information extraction results as Excel table, the sentence list in the HTML result and the highlighted content in the HTML result. |

3.2. Information Extraction

As part of our experiment, we ran the active learning IE system on a pool of 15709 HTML/XML-formatted papers to extract ring-opening polymerization (ROP) properties. Our system was able to extract 1852 records of related properties such as the ceiling temperature, entropy of polymerization, and enthalpy of polymerization from 628 papers. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of our system in extracting complex and specific information from a large dataset. In the following sections, we will provide a detailed demonstration and evaluation of our results, highlighting the strengths and limitations of our approach.

Results Visulalization To assist material scientists in quickly locating relevant material properties and potentially impactful research papers, we developed a user-friendly visualization of the extracted information for easier result verification and correction, while keeping in mind the goal of providing an assistive tool. An example of the visualization is shown in Figure 4. We present all extraction results in a table, which includes the material name, property mention, property quantity, and the original articles and sentences where the properties were extracted. Each article is given an importance score based on the number and type of extracted properties, and the result tuples are arranged in descending order accordingly. The top lines of the table are displayed in Figure 4.

To facilitate label verification and correction, we output the entire article content as a simplified HTML file with extracted results listed at the top (Figure 4) and highlighted in the original paragraphs (Figure 4). The results listed at the HTML top are accompanied by a link pointing to their locations in the article. Such an output comprehensive format shortens the time that material science experts need to check each result item.

Note that the results can come from either labeling rules or supervised models in this step, and the source of the results does not affect their visualization.

System Performance We conducted a manual examination of 101 extracted property mentions from 40 articles. Our system achieved a precision of $62.4\%$, indicating that it is an efficient and reliable information resource. The system has successfully brought many unnoticed articles to researchers’ attention and facilitated the overall research project. We randomly selected 6 articles containing ROP properties and annotated them using our IE system. The articles were evenly split into two batches, and a person with domain knowledge was asked to extract property data points from these two batches, one with the assistance of the IE results and the other without. In total, 4 people participated in the experiment with two having access to the IE results for the first batch and the other two for the second batch. The experiment showed that each person spent 6min 4s in finding a property data point from scratch but only 3min 24s collecting the same data point when guided by the IE results. It indicates that the IE system allows the materials expert to decide if a paper has the information desired or not with relatively high confidence in a shorter period.

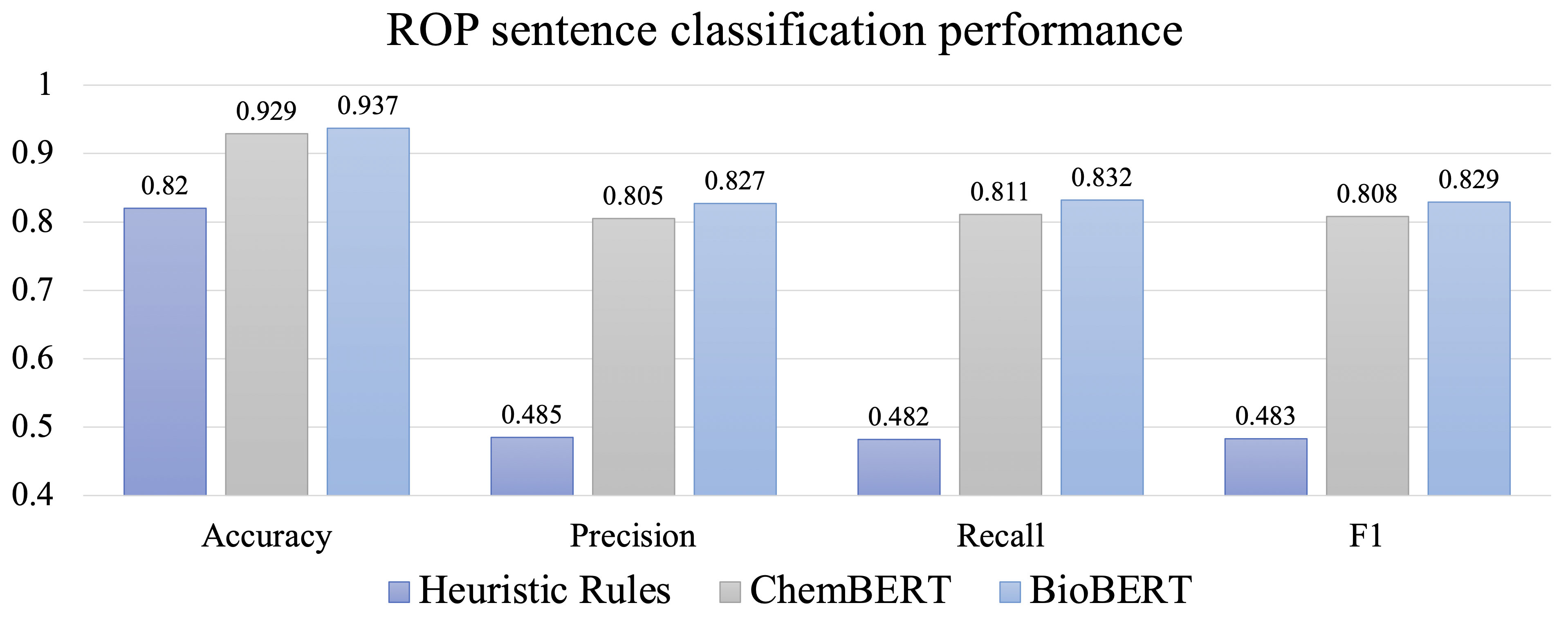

Model Performance To demonstrate the rationale behind our active learning setup, we evaluated the performance of labeling rules and supervised models for sentence classification on a dataset comprising 276 positive sentences and approximately 1300 negative instances. As we will discuss later, the negative set contains around 300 closely negative sentences and 1000 remotely negative ones. This dataset was obtained from the last iteration of our active learning process, ensuring that it includes as many data points as possible to enhance the reliability of our evaluation.

|

| Figure 5. Model performance |

Figure 5 illustrates the performance of the models. The results indicate that the BERT-based models perform significantly better than the labeling rules. This demonstrates the importance of implementing an active learning strategy when collecting an initial set of data points. In terms of performance, BioBERT outperforms ChemBERT. This disparity could be due to differences in the tasks being performed.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a pipeline for material property extraction to complement datasets used for robust property prediction model training. The pipeline is designed to reduce the dataset construction effort by increasing the accuracy of the automatic extractor while minimizing human involvement. For document parsing, we improve the output quality by accommodating the parser to the style and content of each literature publisher. For IE from the parsed articles, we first apply simple and easy-to-access labeling functions to acquire a set of weakly labeled sentences and then treat them as an initialization to a “label refinement–model training” active learning loop. Applied to ring-opening polymerization property extraction, such a strategy successfully find several valid data points which are previously unnoticed by the material scientists. These data points greatly contribute to the training stability and final performance of the property prediction model.

Leave a Comment